A thread. 60 years long. Not old and worn and dusty and long forgotten or ignored and outgrown. Rather it branched out, grew stronger and more complex, twined with others. It tracked across the landscape, connecting and leading me on.

Day 1 Canberra to Cocoparra NP

Minus 3.5 degrees, heavy mist, 95km/h windchill. Canberra bitter winter morning. Warm clothes, full rain gear and over-mitts kept me alive. Heated handgrips on full. The dip past the bottom of Lake Burley Griffin was the coldest.

Butterflies in the tummy prior to leaving home. The bike was big and heavy, then there was a full tank of fuel, camping gear and food, probably too many heavy tools and repair gear. Top heavy. At least I’d made it to the start, rushed and stressed in the 2 days leading up. A slow leaking front tyre led to a rushed drive to and from Sydney to collect a brand new wheel. The old one had a very small flat spot on the rim which meant it couldn’t quite hold the air pressure of the new off road tyre. That the insurance would cover the exorbitant cost was a risk. And so the pack-up became last minute, hectic. This trip meant everything. The decades long dream bike, adventure of a lifetime with my closest friends, the desert landscapes that I loved, attempting to cross the Strzelecki Desert where we had failed seven years before, heading back to Lake Eyre, accompanying Kim through this journey that he had missed on our first planned big trip together, three weeks adventure riding, being alive and able and ready for the challenges ahead. Doubts, misgivings, concerns, lack of confidence, fears. Was I? Were we? Taking on something that was too much for us? (I’m 66, the others – 66, 67, 70) I felt responsible. It was my idea, and planning. Was I up to it? Were we? Butterflies. And also excitement. Later Chris told me he had felt the same as he rode into the unknown at the end of his driveway and entered the road that morning.

Miscalculation – I arrived 45 minutes early. Eventually Kim rode into the meeting spot. Someone had run into his bike a week prior knocking it over and breaking the stand. His prep had been sideswiped. Then Chris, the odd man out with no major unexpected problems to deal with at the last minute. And lastly Marc who had dealt with a tiny puncture in a brand new tyre amongst the myriad wranglings of preparing his new bike and sorting out all his gear and luggage for his first big trip – he’d be riding dirt, with his bike fully laden, pretty much for the first time in 40 years. I think when he arrived there was already the hint of a grin on his face.

Thick mist like rain. Cold. For the first hour my visor kept fogging up unless I left it open a little which let in the windchill. Poor visibility. Traffic at high speed. Scarey and nerve wracking. I started imagining where I might run off the road and crash. It would take several days for this lack of confidence thought process to dissipate. Hard riding, stuck together, stayed in sight of each other where we could, headlights on, concentrated. Then out onto the Hume Highway, we rested, chattered and the mist lifted.

We followed the Lake Burley Griffin Way without much traffic. A lovely country road. Green fields, small towns. My bike purred, silky smooth and relaxed, its warmth spread into me and exhilarated the riding. We were on our way now. Rests and thermos and chat every 45 minutes or so seemed manageable and safe and comfortable – this would become our pattern for the rest of the trip, a main risk management strategy, an acknowledgement of our age, a quiet nod of appreciation to the seriousness of what we were involved in, our need to balance the alone time spent inside our helmets with sociable camaraderie. Harden, Temora, Ardlethan, Yenda. As the road dried out enjoyment of the riding settled in. We turned off the bitumen, let our tyres down a little and rode dirt into Cocoparra National Park. I stood up on the footpegs to practice riding positions, cornering and foot placement. The dirt was easier than the dry sand we had encountered previously – probably due to recent rain and compaction. This was confidence boosting.

By the time we set up camp in the deserted open woodland Marc’s big grinning smile was fully revealed. He seemed just to love everything we were doing. His KTM 790 was a brilliant bike for this trip – seriously off road orientated, a good size while not being too big and heavy, and its very low reaching fuel tank set the center of balance low. “I feel like a kid with a new toy”. (Marc) Later Kim would relate how he had felt thrilled and invigorated riding his first bicycle as a young kid. Half moon. Campfire warmth. Laughter around the mastercampchef table.

Still evening. Surprisingly cold night.

360km Canberra to Cocoparra NP including 20km dirt.

Day 2 Cocoparra NP to Ivanhoe via Hillston

From inside my not warm enough bed I heard the sound of a crackling fire – ooh thanks Kim. Miscalculation 2 – my choice of compact and light sleeping bag should have been instead a comfortably warm one from my collection. I could only hope the weather would warm up a bit as we journeyed on. Muesli, tea, make a thermos of coffee, make a couple of wraps for lunch and sort a few bars and snacks, pack up, check the luggage, clean glasses and visor, peruse the maps, then struggle into all the wet weather gear that would keep out the cold. Fine weather.

We rode dirt backroads to Goolgowi. Squiggly mud, some red sand and gravel. Some of it was a little scarey – no-one wants to fall over in mud or sand. This was a great intro for us. A few days earlier this would have been a slippery mess and in a very dry time the sand and dust would be pretty deep. Luck on day 2. I confessed to the guys that whenever I came to a tricky part my teeth would clench, my face, my arms and shoulders would tense up and in my head I would be saying “Oh, No”. I often look to pick up riding skill tips from the others and the internet – and everything pointed to the benefits of being relaxed when the going gets tough. I told them that I had been practicing relaxing at the hard sections by deliberately doing a big, wide goofy smile, breathing out long and slow and saying in my head “Oh, Yeah.” As I demonstrated they shook their heads and chuckled. I’m convinced that the smiling facial musculature and self-talk and breathing flowed out into the rest of my body. It’s probably lucky no-one else could see inside my helmet at tricky times but I continued this through the trip and the retraining of my neural pathways seemed to work.

Café and correllas by the Lachlan River. Hillston for me is like the frontier town where the outback begins. All roads west are dirt and remote. No-one in town seemed to know much about the condition of our road through to Mosgiel except that maybe the first 20 km was now sealed. Many of our tracks further out, and this road also, had been closed due to rain until the last couple of days so we were concerned to gather as much info as we could. We topped up with water and we had shelter, food, first aid, tools, some spares and a satellite phone in case we broke down or got stuck. It was 100 km to Mosgiel through flat, open, sparse land with only the odd farmhouse. A breakdown or injury could take several days to get sorted out. The first part of the road was easy. Onto the dirt we aired down then set off. After a kilometer or two we stopped together and Chris declared the road surface was good. I agreed but we had 80km still to go. BIG sky country. A car came the other way and we yarned about the road conditions up ahead. The driver said it was “probably” ok for bikes but that there was a long deep muddy section near the end and that our tyres might plug up. A little further on another driver told us he had seen bikes being rescued out of the mud in the last kilometer before the sealed Ivanhoe road. This news was daunting and gave the next long section of the road, which was good, a long time for us to envisage our fully loaded bikes trying to get through a kilometer of difficult mud. A couple of hot shot looking and sounding adventure bikers on tenere 700s said we should be ok. Before reaching this last section we decided that when we got there we’d stop and walk some of it to check it out properly. We reached a section with ruts from 4WDs that had obviously been muddy in the previous few days but were now firm – you just had to be confident, look up ahead, stand up on the pegs and STAY IN THE RUT you selected. So we rode these ruts while waiting for the really muddy part. But soon the intersection sign appeared in the distance and got steadily closer until we exited the ruts at the sealed road. Hmmmmmmm. I know it’s common to get target fixation in these sort of places where if you look at the side of a rut (in your fear or lack of confidence) you will likely steer into that rut sidewall and end up crashing and falling into softer mud on the side (and need help getting back upright and on your way again). This reminded me of 4WD trips where you get very diverse opinions about the road conditions. All you can do is gather as much info as you can and then either give it a go, with the idea of turning back if it gets too hard before you get committed and in too deep. Or you decide to take a different route altogether. This was all rolling through my mind as I considered the major decision I thought we’d have to make later that evening.

It had been a good day of dirt riding. We aired up and rode the blacktop for 50km. Ivanhoe is an iconic very small town, often in summer the hottest place in NSW, and in the middle of huge arid country between the far distant Murray River in the south and the Darling River in the north. One gas station, one small shop, an RSL club, a small medical facility, a camping ground and 160 people. Long, committing, enticing dirt roads head north west to Menindie and south west to Mungo. Soft grassy camp, hot shower.

RSL dinner and beer. We had been following the South Australia and Sturt National Park outback roads status for several weeks. Most of our roads had been shut due to rain for long periods. When these dirt/clay/sand/gravel roads get significantly wet they get cut up badly by 4WDs and trucks such that the agencies that maintain them have to do lots of grading and repair which is expensive and time consuming. Not to mention that idiots get bogged and need rescue after they slide off the roads. So there is a system of gradual opening to lighter 4WD vehicles, then 4WDs with towing, then to light trucks and finally heavy trucks as the roads dry out. One of our key roads from Cameron Corner to Merty Merty had only just opened to 4WDs with no towing. This indicated to me that the road could still be slippery, with water crossings and some issues – all of which are relatively easy in a 4WD but on a heavily laden bike could be problematic. I didn’t want to be picking my heavy bike up out of mud lots of times. I was worried. This is where sand had been a problem for us in the past even though we had made it some way along before a radiator blew on one of our bikes. The sand was a second but ongoing concern for me on my now heavier rig. We calculated we would each need to carry at least 6 litres of water and an extra 5 to 8 litres of fuel for the two day, 490km dirt ride between Cameron Corner and Leigh Creek. The other guys would have heavily laden bikes too but would not be as cumbersome as mine. It was decision time at Ivanhoe because the following day would take us up towards Tibooburra and the Merty Merty Road and the Strzelecki Desert or we could turn off and bypass that whole section and ride to Maree through Broken Hill and the Flinders Ranges. Our previous failure up through the Corner weighed heavily. We decided to push on to Wilcannia, the turn-off point, make a few key phone calls to get as much info as we could and make the final decision. We had gone all the way up to Stockton Beach a few weeks prior to practice sand riding (I had failed in the deep sand). I was afraid to be the one to lack confidence and be the one to turn the team around. As a back-up we could give it a go and then turn around if it got too hard, though this would compromise the rest of the trip by having to backtrack.

I tossed and turned in the freezing night. In the darkness before the dawn my anxiety peaked.

Cocoparra NP to Ivanhoe – 290km including 160 on dirt

Day 3 Ivanhoe via White Cliffs

Thick frost on the tent, on the bike seat and crunchy white frozen grass. We broke up the ride to Wilcannia into three 60km sections to keep us fresh and manage fatigue. One of our group had crashed badly a year previously when solo riding along the Oodnadatta Track – possibly due to a micro sleep. During more than 150 days of riding together on trips as a group we have only had one serious crash. I find it very useful to know ahead of time that no matter who is riding up front that we are planning to have a break at a certain time or distance or place.

There was quite a bit of wildlife on this section and roadkill at regular intervals. Flat arid country with often only one side of the road fenced. Cattle roamed occasionally on the road side. Where drainage lines crossed the road dipped slightly and scrubby vegetation grew higher, more densely and closer to the road. Whenever there was a dip like this I slowed down and rode the middle of the road as I assumed the chance of wildlife was greater and less visible – there’d be less time for evasive action. In those 150+ days we hadn’t hit any wildlife. In the open plains and desert country where the vegetation is less than knee high you can see wildlife a long way off but in more dense scrub and forest it can be like Russian roulette at times. We agreed on a hierarchy of animal road sense. Goats are numerous in some places but seem to be aware of staying away from the road. Cattle are large, slow moving and generally easily seen and avoided. Sheep seem somewhat aware of the road but when in mobs can be unpredictable and move fast. Kangaroos like to hop along the side of the road or jump out randomly across the road – there were regular big reds rotting, smelly on the roadside. Emus are ridiculous – they run along at speed beside and then on the road and can then just stop right in front of you or sprint erratically around on the road singly or in groups. Risk awareness and vigilance. I ponder from time to time the effect on me and the group of one of us colliding badly with an animal. I know we all understand and personally accept the risks involved in what we are doing but I still ponder and project forward into possible futures. Adjust the speed in relation to the surroundings and conditions, be alert to changes and adjust in an agile timeframe, remain aware – these make up part of our safety net and also are probably part of the reason we ride – to be acutely alive in the continuous moment of the ride through life.

Wilcannia. Our crossroads. The Barrier Highway heads west to Broken Hill and east to Cobar. Green park by the struggling Darling River. Café, lunch, rest. Our little speaker blared out “Mango Pickle Down River” by the Wilcannia Mob kids from 2002 when it had been a hit on Tripple J – “when the river’s on we jump off the bridge, when we get home we play some didge”. I called Sturt National Park – the road to Cameron Corner was open and in pretty good condition. Chris called the Cameron Corner store – the Merty Merty Road was ok, it had been open for a couple of days and although only open for 4WDs with no towing people had been coming through with caravans and even a road train. Good news. The weather forecast was still good for the next week though continuing very cold due to a blast of polar air from the south. The day was warming up very slightly under a weak sun. “We rise to a challenge and set a course. We take a decision. You put your mind to something. Just deciding to do it gets you halfway there. Daring to try.” (Tim Winton) We would head up there and give it a go.

Driving on roads that are closed to you is risky – your insurance is invalid, you can receive a heavy fine and you might significantly damage the road.

While I filled up at the petrol station an old car pulled up at the next pump. A young Aboriginal kid smiled at me and asked about my bike and whether I had a name for it. I told her it was called Lupin after the blue colour in the manual (I’d never heard of that colour before either). She told me about her bike at home and then about her pet dog. We laughed together while her Mum filled up. I asked if her dog had a name. “Bluey”, she said and then she jumped out of the car and ran around to my side, hugged my leg then scampered back in and the car drove off as she waved. I’ve called my bike Bluey ever since.

Blacktop for 90 km to the opal mining town of White Cliffs. Trepidation about the next few critical days ahead. The bike purred along. My imagined crash scenarios had dissipated. At times I felt like twisting the wrist and ripping along instead of ambling along at ease at 95 km/h. Easy riding.

Set up camp. Beer at the pub. Dinner, warm fire.

Ivanhoe via White Cliffs – 280km

Day 4 White Cliffs to Tibooburra

Great dirt riding for 140 km through delightful landscapes of white gibber, massive green plains from recent rains, a mob of brumbies that galloped alongside Kim, a low range blue in the west. It felt very remote. More traveller cautionary stories of a bike down in the mud near the end of the dirt – the difficulties never eventuated (again) – maybe this was a case of car drivers underestimating what our bikes and us were capable of. We joined the now sealed Silver City Highway at the spanner tree where a section of the highway doubles as an emergency airstrip. Then short stints to Tibooburra.

We fueled up, searched out a few food items to top up our supplies for the next 3 days, set up camp, cooked in the camp kitchen in drizzle. Hot chocolate. Bed at 8.30 pm became a habit – sunset at 5.45 pm – it’s a long night. We all (except Chris who brought his WARM sleeping bag) worked on strategies to keep warm overnight – Marc folded his insulated groundsheet under his mat, Kim pioneered zipping up his jacket and putting the foot of his sleeping bag inside it, I took the lining out of my riding pants and wore them to bed with the thickest socks I had and a beanie on inside the hood of my too thin sleeping bag.

White Cliffs to Tibooburra – 250 km including 140 km dirt

Day 5 Tibooburra to Cameron Corner

I’d been anticipating, for the last 7 years, that this and the next day would be crucial for the overall journey we had planned. The last time we had ridden to “The Corner” the last 15 km had included quite a lot of sand and having had virtually no sand riding experience we had struggled, not fallen off, but been scared and with the bikes underneath us seeming to move independently, squiggling from side to side, like they were finding their own way. We had managed this by standing up, looking forward and keeping momentum up. Now I was on a bigger, heavier and perhaps less capable bike. We had done loads of riding dirt and some sand in the interim.

At the coffee shop we chatted with a group of adventure bikers who had just ridden out and back to Merty Merty loaded up. They looked pretty pro but told us that in their opinion the road was pretty good, that there was not much sand, just one really sandy section at a claypan detour and that there were some rutted washaways on the steeper western sides of the dunes past Cameron Corner that required slowing down over the crests. This was reassuring though every rider’s opinion is relative to their skill, experience, bike and the speed they travel at. Some adventure riders have ridden motocross, enduro, trials or trail bikes in the bush or even in competitions for decades.

We set off from the Tibooburra sign into great dirt riding. “This has got a bit of everything,” Marc. Flat 360 degree gibber desert plains, grassy fields, gravel, hard packed clay, DRY, corrugations, the “Wide Open Road”, small jump ups, scrub. Flowering plants, zebra finches, clouds of budgerigars. At a huge claypan we found a detour round the side of a small lake. We rested and photoed before committing, expecting difficult sand. It turned out to be sandy and squiggly but quite manageable for each of us, albeit with a quick switch on of focused attention and a dose of commitment. As we neared The Corner and entered dune country I expected to see the slight curving rises of tricky sand that had been etched into our collective memory. They didn’t eventuate – just hard packed clay over low dunes of red sand. Pretty straightforward. WHAT a surprise so far.

Camp was set up on the “Corner” where NSW, Queensland and South Australia intersect. The people at the Store/Pub/Camp ground were lovely. With unladen bikes three of us rode out and checked the first 15 km towards Merty Merty. It was the same hard packed clay over even the higher dunes. There were some rutted washaways but all was entirely manageable. With smiling confidence we rode back to camp. Shower, fueled up and filled our extra fuel bags, bore water. The cold breeze that blew each day died off under a coloured sunset, as it had each evening. Dinner cooked at the camp kitchen (freeze dried packet and deb again) and a group fire, tales told by 4wd tourers. The moon rose as the sun set. Hot chocolate. 8.45 pm zzzzzzzzzzz

Tibooburra to Cameron Corner – 140 km all dirt

Day 6 Across the Strzelecki Desert

Our regular morning routine had evolved into waking at about 6.30 am, packing what we could and dressing in the tent, breakfasting as the sun rose around 7.30 then packing the bikes and setting off around 9.00. The distances meant we didn’t have to rush but we kept things moving efficiently. Each of us tried to develop routines for where everything went in the luggage and how bags were fixed to the bikes. Nearly every day we rode in all our warm gear with wet weather jackets and pants over the top to keep the cold out. It should have been warmer out there. Maybe the cold was the price we paid for the continued stable weather.

The Strzelecki Desert was a massive flat expanse of rolling dunes. The red sand dunes ran north south so we were crossing them all on our westward ride. The prevailing wind is from the west which causes the windward side to be steeper than the eastern side where the blown sand settles. Between the dunes was a flat area where finer particles settle with dust and sediment. Across these flats the track skirted occasional remaining muddy sections and was primarily flat, hard clay. The runups to the dune tops were often a little rutted but easily managed and then we would slow down to scope out the run down the steeper sides which often did have minor washaway furrows that could have been dangerous at speed. At a slow speed the furrows were not a problem. The sand on the track was almost non-existent. The riding was straightforward. Chris figured out that the last time we had attempted this crossing was during a long period of drought. The hard pack would have dried out and the surface disintegrated back into soft sand as a result of traffic and heat. We surmised happily that with recent periods of wetter conditions the soil and sand became bedded together and the traffic then compacted it into firm clay. Also there had been 7 years of occasional grading and trackworks.

Endless fields of yellow. Such a profusion and diversity of plants when you walked away from the track and looked carefully.

Seven years of anticipation and trepidation. This was the reward for our gutsy decision to give it a go. I could have ridden that dune country for days. Westwards the dunes grew in height so that every cresting revealed a larger vista of flowered sandy ripples stretching towards the distant horizon. The undulating track snaked its’ way ever onwards. I felt dolphin-like with Bluey, like I was swimflying over the swells of some ancient desert ocean. Elated. A wonderful sense of achievement. Deep gratitude that I was there, riding the adventure of a lifetime, that I could do it, that we could do it.

Eventually the track turned northerly and ran on the long flat between the high dunes. We rested and lunched in a an open, treed flat of darker soil. I hiked to the top of the closest dune for some quiet moments alone, off the bike. Stillness. Views all around, red sand, tussocks and flowers. Blue sky, sun, warmth.

Past the Merty Merty station homestead fields of purple appeared. Just short of the junction with the actual Strzelecki Track was a really nasty cattle grid that I thanked all my lucky stars did not seem to have bent my new front wheel rim. High fives, hands shaken. This had become a later life goal – riding across with Kim and Chris. It had been a long time coming and at times it had seemed a very distant possibility. I wondered how Marc felt having chanced into the team at just this right moment. Like Chris, 7 years before, he had risen to the challenges and was embracing the whole odyssey brilliantly.

The “Strez”, wider, regularly maintained, hard packed smooth clay, gravel, and corrugations, is one of the main access tracks into the remote Moomba gasfield 60 km further north. Heading south we encountered huge oncoming road trains with 3 trailers. We pulled off to the side of the track and waited safely while they thundered past. There was some high speed dirt and a few short sections of tarmac. Very few other vehicles all afternoon. Out of the dunescape.

Montecollina Bore is one of the few recognized camping places on the Strez. Weird lunar landscape of fine white sandy soil, no facilities or drinking water although there was a small lake in the scrub. The bore had been capped to protect from leakage of the diminishing Great Artesian Basin supply. I dropped my bike trying to maneuver at 1 km/h over soft, lumpy ground. This is the sort of speed and situation where the big, heavy bikes are most cumbersome. The others helped lift back up. In the old days I’d have earned the “Strzelecki Cup” for such a blunder. And even worse I realized I’d LOST MY FAVOURITE THERMOS out of the back pouch. UGH. I really loved sipping weak coffee at each morning rest stop in the cold.

Explore the surroundings, warm fire, dinner, photos, moon, stillness, quiet, no-one else for a long way, happy chatter, hot chocolate. Dingo groups howled to each other from three locations around but distant from our tents – wildly wonderful. Calm, relaxed, peaceful sleep.

Cameron Corner to Merty Merty (120 km) to Montecollina Bore (110 km) – total 230 km all dirt

Day 7 Montecollina Bore to Farina

Corrugations, gravel, hard packed clay. This was a long hard ride that we cut down into 30 minute sections to ease the grind. Occasional tar bits were a delight. The landscape changed regularly between wide open flat stony plains, desert river beds and low plants. The blue green Gammon Ranges rose way out to the south east. A really nice song from our early family travels to central Australia popped into my head – “Raining on the Rock” by John Williamson – “red and blue to burgundy, we’ve just come out of the mulga where the plains forever roll”. This was nice, bringing back memories and also beautiful, iconic images HOWEVER it became an earworm for the whole rest of the trip. At first it was fun trying to piece together the other lyrics.

It was a relief to finally reach Lyndhurst after 225 km. We all still had plenty of fuel left to reach Leigh Creek – our consumption had been less on the slower dirt tracks.

Internet revealed the closing time of the famous bakery at Farina. By this time we were airing up with hand bicycle pumps as two electric pumps had both died. We ramped it up a bit down to refuel and visit the supermarket at Leigh Creek. Oh Damn. It was Saturday and the supermarket was shut. I did get a replacement thermos at the gas station though – celebrate the small wins – and filled up our water supply. Bitumin to Farina. The bakery deserves its legendary status – there are loads of happy helpful volunteers to make coffee, sell breads and pastries and finger buns and cookies and cakes and pies – all from a historic underground oven. The ruined remains of the once thriving small town that serviced the Old Ghan railway lay all round. The camping was delightful. The wood chip water heater delivered hot bore water showers. Fire, dinner. Coincidence of the moonrise and sunset. The team was just humming – everyone was generous, flexible, sharing, supportive and caring – the days were full but I think we were all so engaged with it all that we just wanted the whole of the trip to be great that we were being our best selves individually and for each other and together. We all had our own struggles that we dealt with – at our ages some things are just hard (getting out of the low camp chair, sleeping, the cold, aches and pains etc etc) – and we pushed through into this journey that was turning into a real cracker, a treat, something very special. Our group culture was strong, almost tangible. This is one of the main reasons “why we ride”.

Montecollina Bore to Lyndhurst – 225 km to Leigh Creek – 40 km to Farina – 60 km. Total 325 km including approx. 200 km dirt.

Day 8 Farina to Coward Springs

The 70 km run from Farina up to Maree had been high speed hard packed dirt on past trips but was now black top. Comfortable, easy, relaxed riding, just tuning in and slowing down at the depressions where the vegetation was more dense and closed in on the road. Fuel, water and a few items of food at the small roadhouse (our last for 4 days until we reached Oodnadatta).

Out of town we called Geoff, a close friend of us all and a key member of our riding group until 18 months prior. He had rediscovered his love of riding through the group and then over a couple of years he rode with us on various trips. He had owned a number of bikes in that time including a DR 650, KTM Duke 390 and then, sparkling with enjoyment, he rode his dream machine, a Moto Guzzi 850 Travel, on our group trip through Tasmania. At the end of that trip he continued up on his own towards Darwin while we returned to Canberra. I received a dreaded call from his wife a few days later. His emergency tracker had gone off – he was in an emergency out on the Oodnadatta Track west of Maree. He had crashed and was taken to Adelaide hospital. Over the next several months he slowly recovered. The bike was written off. He agonized for a while about how to move on and in conjunction with his family decided to ride no more. We had all shared with him his love of being part of the group, riding and journeying through the landscape. We understood and appreciated his decision. I felt partly responsible having introduced him to the group and lent him my bike for his initial clinching rediscovery ride. Unlike Kim, who had been a long-time rider and got back into riding after retirement at the same time as me (something we committed to together), Chris, and then Greg and now Marc had all joined in the action following my invitation and support. Greg had come on several desert trips on a DR and later even ridden his own Harley before also deciding to ride no more. Speaking together with Geoff from near the scene of his accident was painful and a little awkward. I think he got the message that we respected his decision, that we acknowledged how much he would have liked to have been with us, that we were so glad that he was still alive and in good nick and that he would always be a great friend. We rode off with an inner quietness, carrying part of his presence with us. In a later group conversation where we confronted the unthinkable I surmised that Marc spoke for everyone when he said that he just appreciated and enjoyed riding so much that he took 100% ownership and responsibility for his decision to straddle his bike, twist his wrist on the throttle and ride into adventure. For each of us the rewards outweighed the risks.

And unexpectedly we rode straight into one of the hardest parts of the trip. The last track grading must have been quite a while ago. The corrugations were horrendous and interspersed and mixed with skittish gravel. You just had to accept the punishing that the bikes took – and hoped the engineering was designed to withstand it. My brain and teeth chattered. Standing up helped ease the impacts a little. Everyone has their own ideal speed in these conditions – it’s a complex combining of confidence, skill, bike design, weight and distribution of luggage, experience, risk aversion, patience, tolerance of difficulties, tyre type and pressures, load, discomfort and approach. At higher speed it’s sometimes possible to almost float along the tops of the bumps but then things happen faster. At slower speed you can feel every bump in full and get shaken apart but you have more reaction time for the unexpected rock or gravel patch or hole. Often there’s a car wheeltrack or two that is clear of gravel to ride along but then there are times when you have to cross a line of gravel to change to the other wheeltrack – this is often sketchy. We settled into a corrugation and gravel routine with Kim and Marc most comfortable at higher speed, Chris in the middle and me bringing up the rear. The front two would stop and wait periodically so as not to lose touch with the rear of the group.

The Oodnadatta Track, now a popular outback 4WD tourist route followed the route of the Old Ghan railway line. There were ruined rail tracks, bridges and stations at regular intervals. It also followed the route of the cameleers that serviced the cattle stations prior to the train line, the original telegraph line from Adelaide to Alice Springs and Darwin, the route of the early explorers and also the trading routes of the Aboriginal people who linked up the network of natural springs fed by the artesian water underneath. This is a rich story line through the landscape.

At what must be the remotest sculpture park in Australia I thought about the wars in Ukraine and Gaza next to a rusting model bomb adorned with “No More Bombs” and a peace sign. We had been almost completely away from any news for more than a week now. The rest of the world seemed far away. We were completely caught up in our own world. When we passed through small towns and had reception we checked the weather and called home and then resumed our journey.

The first glimpse of Kati Thanda (Lake Eyre) South is dramatic. It seems to hang in the distance. White and surreal. We rode off the Track to two mound springs – avoiding shocking corrugations by slithering along a tricky, sandy side track then across a streambed.

The worst corrugations were in the last 20 km to Coward Springs. This is a haven, isolated but comfortable. Lovely people. Purchased a fire’s worth of wood. Date plantation – date scones, date jam, date cake and more. Warm spring to bathe in. Wood chip shower.

The weather forecast indicated the possibility of showers in about 5 days time. Our plan had been to get onto the highway (black top) on the 5th day so we altered our plan by cutting our stop out at Kati Thanda (Lake Eyre) to 1 night rather than 2. This would give us a day up our sleeve to be off the dirt when the rain came – slippery, closed roads were not a good place for us to be. The forecast did indicate though that until then our planned trip was all going to be clear of bad weather – amazing good luck (or so it seemed).

Brilliant sweeping sunset then beautiful moonlight through high clouds.

Farina to Coward Springs – 210 km including 140 dirt

Day 9 Coward Springs to Kati Thanda (Lake Eyre)

It had been a rare warm night and delightful sleep. Dawn blazed the sky with orange, gold and pink as we packed up.

Marc got a message that the son of a friend of ours had suicided the afternoon before. This is the absolute worst thing for a parent or a family member. The rest of your life would be one of utter sadness and the deepest trauma. Were the other children vulnerable now too? Three of our group of four were also parents who felt they had come close and been on suicide lookout at times with our own children – we had had fears. Was it mental health? We called our friend and shared our compassion and concern. I don’t know where he found the wherewithal to ask how we were going and then to say that what we were doing was great. I thought much about what he might have meant by saying that in his time of such darkness. Was he referring to our small group friendship, our team, doing something amazing together, challenging ourselves on a big adventure, spending so much time immersed in the awe-inspiring desert landscape and the outback countryside, to feel the exhilaration of riding …………. And then I considered if only we had had an opportunity to share some small part of all this with his son, with our own sons, our own daughters.

Back out on the Track the going was easier. I rode slower, in a sombre state of mind, torn with the idea of heading further away and not towards home and our friend and our shattered wives who were much closer to the mother. It would take at least a week to ride home and in a few more days we’d be heading that way anyway. Attention was drawn to focus on the gravel, the stones, the patches of corrugations, the claypans, the salt flats, low dunes, gibber fields – the desert. A dingo loped along the Track in front of me for a while then hopped aside and watched me pass then followed along behind, alone.

At William Creek we refueled, topped up our water supplies and lunched. Kim and Marc did a flight over Kati Thanda and came back bubbling with it all. I talked to Cath who was in Johannesburg, stressed, exhausted and smashed, from the news at home and her trip difficulties.

The 70 km track out to the camp at Halligan Bay on the edge of Kati Thanda reputedly had been worked on recently and this work was ongoing. I knew that whatever the road condition the ride would be totally absorbing – environmentally and technically. We were heading into an enormous low depression below sea level, perhaps the harshest part of the continent, remote, unforgiving, wild. The end of the line for the Cooper and Diamantina Rivers, when they flowed. Part of the mythology of Australia. The dead heart. Mesmerizing. Salt. It seems timeless, where time stands still. Where you feel tiny and fragile. Arabunna country.

The section of shallow sand about 15 km in still demanded attention and a fluid standing style where you looked well ahead, kept momentum up and let the bike snake along underneath, thighs holding the tank. Then easy riding to about half-way in, to a memorial built for an Austrian tourist who had tried to walk out (first mistake) from the camp after getting bogged in soft sand – it had been 40 degrees in the summer (second mistake) heat. The country turned into gibber plain, black and brown, haunting, not a stick of vegetation. We stopped at an overlook where the scene stretching out below was reminiscent of Mordor from my younger adult imagination. Stark, not dead as such but lacking any life. In the distance white salt, flat to the horizon. We followed one another down into an eerie land where the track twisted between small black, stony hillocks. For a while we played roulette, dicing between the smoother wheel lines off the side that were sandy and the track itself that was heavily corrugated. The workers hadn’t got that far. For the second last section we rode along the flat track beside the salted, dry lake bed itself, no water to be seen, only white. The final challenge was a longer run of deeper technical sand – it had been a short day of actual riding, we were fresh and tuned in – and we made it to the camp without mishap.

Our campsite was away from the few other vehicles that seemed to be attracted by proximity to the loos, crammed in together. We had a clear space in among some sandy bumps behind the low grassed lake edge dune line. The breeze dropped as we set up tents and boiled a billy.

Just before sunset we silent walked our own paths along the lake shore, each of us alone, but together in our solitude, contemplating life and the universe and death. It had been at this hour the day before that the young man had tragically departed. Among standing waist high grass tufts we watched a parade of colours across the dome of sky, out on the endless salt and amongst the plants that hugged the lake shore.

The change from day to afterglow and evening. Moonrise. Glittering stars. The emu in the sky stretched out from the southern cross right along the Milky Way – many Aboriginal groups believe that these stars are campfires of some of the ancestors that have passed before, waiting by the river in the sky. Later the moon reflected off some distant water on the eastern horizon. Warm, still, quiet night.

Coward Springs to William Creek to Halligan Bay on Kati Thanda – 140 km, dirt

Day 10 Kati Thanda (Lake Eyre) to William Creek to Algebuckina – 220km all dirt

The night had been comfortably warm. Predawn stillness. Stars faded into morning glow then sunrise, from the edge of the salt flat. Colour, like fire, radiated from the east.

Our bikes had stood up to everything we asked of them. And so had we. We chattered a lot during each day, it was a nice contrast to the hours we spent alone inside our helmets. At some moments we shared stories of our journeys through life. Bathed in shining orange light over steaming tea and porridge we discovered that we had each taken a second shot to get into university. I sensed that the awe-inspiring and humbling landscape was gently suffusing our precious, comfortable camaraderie – the mutual trust and friendship that was deepening and growing as we shared this time together.

Oftentimes on adventure trips the bad things tend to happen straight after lunch or morning tea. You relax, take it easy, let your guard down, cool down. You are not warmed up, not tuned in, not focused, not confident and you tense up. Straight out of camp was the most difficult sand section. I was psyched for it. I headed out first and snaked my way through. By the time I could stop I was about a kilometer down the track. No-one behind. One of our main safety strategies was for each rider to keep in touch with the rider behind. High beam enabled us to ride at a distance that allowed the dust to settle and not feel squeezed up. If the person behind wasn’t visible you slowed down for a bit to let them come back into sight. And if they still didn’t appear then you would stop and wait for a short while, usually while they adjusted their luggage or sorted out something minor. And then if they still didn’t show then you turned around and rode back to investigate. Time went by. I switched off the motor. Waited. Then waited a bit longer. Something had happened. It was hard to turn the heavy bike around on the narrow trail. As I rode back scenarios went through my head – crash, accident, injury, damaged bike – it seems the worst possibilities are the ones you focus on. One bike was down on the side of the track in sand and the other two were parked nearby. We lifted the bike up and checked our rider – he had a sore ankle from where the footpeg had landed on him but was otherwise ok. Without enough momentum and at too slow a speed he had gone down. The bike seemed ok apart from a luggage strap that had broken. Our protocol was to rest for a bit, have a drink, double check everything then have the rider ride in the middle of the group for a while. After a kilometer we stopped again to check the rider and bike. All seemed ok to continue. If it hadn’t been ok this was a very remote place to get rescued from, like most of the rest of our route through the desert country. The ankle didn’t look good. The rider was a stoic for sure. He told us that in his youth an older rider in his trials/motocross/enduro club had told him “What do you think your right hand’s for? You’re wallowing around like a hippo”. He admitted to falling off at a very slow 5km/hour and that he hadn’t been awake enough to stand up on his bike in the sand.

Squiggling, corrugations, Mordor. The rest of the way out was fine until the last 2 km before the main track. The team of workers was busy grading the dirt. At the right hand side of the track was a long ridge from the edge of the grader blade – too high to ride through. The grader was coming towards us on the left. Between the grader and the mound was a several meter wide long strip of deep soft soil. There was nothing else to do but commit to riding through trying not to target fixate on the grader or think about how hard the driver might laugh if I went down. Gulp. Throttle. Momentum. Stand up. Balls of feet on the pegs, heels down. Lean a little forward. Look up and ahead. Knees and thighs holding the bike firmly. Relaxed arms. Elbows out. Goofy smile. “Oh Yeah Here We Go”. The bike found it’s own way like one of the giant worms in Dune. The hardest riding of the trip so far. We laughed in wild relief at the crossroads at the ridiculous surprise we had just encountered. Oh the joys of the unexpected!

Back at William Creek we fueled up, coffeed ourselves, replenished our water supplies, rested and checked on the weather which was still all clear for the next 3 days. Back on the Oodnadatta track through the afternoon was mostly good dirt. The country was a diverse and everchanging mix of gibber plains, dunes, purple ranges in the distance, flats and undulations, desolate sections and bushy parts. We sidetracked to more ruined railway stations. The Old Ghan line followed intermittently beside us. At the huge old Algebuckina railway bridge we camped by the pools of the Neales River. Dinner, fire, hot chocolate, bed by 8.30pm.

Day 11 Algebuckina to Oodnadatta to Arckaringa 140 km, all dirt

As we age camping gets harder. Getting in and out of the tent, rolling onto knees to get up from our low slung seats, bending over so many times, cooking on the ground, setting up, taking down and packing up – every day. The physicality of riding and camping was constant. We all knew though that it was all good for us though, for strength, flexibility, endurance, fitness. Every day we were up at 6.30 am, well before sunrise. We would start riding by 9.00 and be finished by 3.00 or 4.00.

We had another luggage issue just out of camp. The Pink Roadhouse – famous outback store – in Oodnadatta was doing a brisk trade in coffee, cakes and various food items. I had a lovely chat with a twinkly eyed old lady Pitjantjatjara custodian who said we were welcome in her country. In the Painted Desert we spent time just taking in the scenes – multicoloured hills, drainage channels threading through the plains. We hiked up to a high vantage point among the hills. It is a lonely, starkly beautiful land that just cries out for you to spend time to explore. Riding on down through this work of art felt like a grand finale to the desert part of our journey. Then just before Arckaringa Homestead was a soft section of deeper gravel and sand where we nearly came unstuck. Two of us would ride back across this section twice more to collect firewood later.

There are two special aspects of a stay at Arckaringa. The communal fire, hot shower and washing facility were very welcome. In the cold night the stars and moonlight were magnificent. The Milky Way and the Dark Emu stretched across the full expanse of the sky again and backdropped our camp. The gum trees and moonlit tents appeared as if painted in by Tom Roberts or some other master artist.

Day 12 Arckaringa to Coober Pedy 140 km including 90 km dirt

Reluctantly we turned toward home, south-east to Mt Barry and then south to Coober Pedy. Much of this dirt was sketchy due to loose gravel and corrugations. We each tried to balance safety with minimizing the juddering and staying in control. I was conscious that this was the last dirt riding that we would be doing and eased off to ensure I wasn’t pushing my envelope so close to the safety of the highway. 50 km out of town we hit the nice smooth blacktop that took us in through sparkling gypsum amongst the flat gibber country. As you do in the opal mining town we had dinner underground.

Day 13 Coober Pedy to Pimba 370 km on the highway

To manage fatigue on the highway we rode in 60 km stints then had a break, thermosed and ate. Over the next 5 days there would be thirty of these 60 km sections to get us 1900 km back home. During the time I spent in my helmet I planned my next few artworks and tried to explore their details and challenges. We got to Pimba in good time in 6 stages at around 100 km/hour. We were still tired at the end of the day. Donga living was necessitated by a forecast of windy rain overnight. This was a luxury after 2 weeks of setting up camp every night. Heavy rain set in at about 2.00 am. The desert tracks we had been on closed for the next two weeks. The weather window we had lucked into seemed magical – we couldn’t have scripted it any better. Our only downside was a wet, cold ride for a couple of days.

Day 14 Pimba to Burra 370 km on the highway

Under full wet weather gear we bulked up with as many layers as we could fit to stay warm. Rain out on the highway. Oh bliss were the heated hand grips. Following road trains was despicable. They sent up thundering white walls of spray that combined with the rain. Oncoming cars appeared out of this maelstrom from time to time as mad impatient drivers in front of us played Russian roulette as they tried to overtake the road trains. We just slowed up and waited out the 60 km then looked for a pull off. Kim peeled off to stay with friends and make his own way home later. We booked into a cottage at Burra and arrived to a fire burning in the lounge, warmth, electric blankets – the comforts of home. The rain continued. 12 sections done.

Day 15 Burra to Robinvale 420 km on the highway

Eastwards along the Murray River. Rain on and off all day. Looong straights, wheat fields, into the mallee, saltbush. Long lines of thought in the helmet head. 7 sections. Back in the tent this time by a river. Camp kitchen – nice.

Day 16 Robinvale to Narrandera 380 km on the highway

Cold, clear, straight roads. Across the Hay Plains. Over several hours I kept returning to ponder what I had read recently from Mark Barnes’ book “Why We Ride”. It had really opened me up to the deeper and diverse aspects of motorcycling. My gut had told me that we were engaging in something pretty special that non riders might find hard to grasp. Learning new things and developing mastery is one of my all-time favourite pastimes – techniques and skills of riding, which for this trip was mainly dealing with the sand, learning how the bike works and fixing things, problem solving which we had mainly done in our final preparations. There’s a line or a continuum between risk and safety that we step into every time we start the motor and set off. It’s not like blindly chasing an adrenaline rush, it’s more like being fully aware of the risks involved and seeking to still ride into the myriad challenges but using all our skills and experience and judgement to make it through, to complete the journey, to stay upright (mostly). Peak adventure is where the level of challenge and risk matches your level of skill. In peak adventure we ride to be fully alive, not bored and complacent or scared shitless because of mortal danger. Exhilarating. If the people “click”, if we come with energy and a shared goal, if we trust and care about each other, if we are generous and supportive, if we are inclusive, if we are flexible, if we are honest , if we are open, if we have fun together, if we share the responsibilities – then the group becomes synergistic, something bigger and deeper than the sum of its individual parts. Our comradery grew as we journeyed into the heart of the continent. Often with a bunch of blokes this is hidden but in our group you could feel it crackling and bubbling just below the surface – we got to experience the best of each other. It might seem odd to associate motorcycling with being in nature but when we are riding through the landscape we feel as though we are really in it, raw against the wind, immersed in the natural world – not like you are in a bubble passing through when you are in a car. And when off the bike we are always right there in the sunset, in the sunrise, in the cold, in the rain, in the heat, in the sunshine, under the canopy of stars, sitting by the fire, hearing the dingos howl, watching the birds – so much awe and wonder every single day.

“When you’re surfing you’re not thinking about where you parked the car or what you’re going to do when you grow up or what you’re going to buy when you’ve got lots of money. You know, you’re just there. You’re in the moment. And I think in a contemporary world, that’s a rare privilege.” Tim Winton. (he could have said, riding, climbing, kayaking, dancing ….)

“We had no news. It didn’t seem relevant out there. The journey was all encompassing.” Kim

Our adventure became everything, except once when the outside world tumbled in upon us and then became part of our journey. We entered a state of being almost completely lost in what we were doing. Time seemed like “it comes and goes in waves and folds like water; it flutters and sifts like dust, rises, billows, falls back on itself.” Tim Winton. We had periods where I believe we each became one with the bike and its movement, where our attention was totally focused. Like other mythical journeys into the desert everything else was stripped away and like Tim Winton’s notion of fluid time so a dynamic state of flow enfolded us. (With thanks to Mark Barnes and Tim Winton for helping me in my struggle to articulate this.)

In Hay we coffeed with two Harley riders who had come down from Cairns and who had already ridden 400 km that morning and then were going on for another 600 km to their destination that night – not my style of riding but respect to them for what they were doing.

Along more straights to Narrandera I struggled with the idea of climate change and how our adventure biking fitted in with it. At its simplest level it was just a different form of tourism. On the bikes our emissions were less than a car, though if we all fitted in one car that would be more efficient. Our journey wasn’t necessary, just plain pleasure. Did our time in the natural world make us more motivated to contribute to environmental actions or donate to causes? Solar panels and a battery at home? Was it just assuaging our guilt if we paid to offset our emissions or did it make a real difference? Was motorcycling (or motoring in general) for pleasure an outdated pursuit that may have seemed ok before global warming? How could I continue to justify it? Were our days numbered? How long could I ignore the writing on the wall? There would be so much that I’d miss.

This was our last night in the tent. Cold again.

Day 17 Narrandera to Canberra 360 km on the highway

Cold riding all day. We found a glorious back road to Gundagai – no traffic, winding, undulating, scenic, at peace with the world, rolling through the countryside. Usually towards the end of a big trip I would feel flat but instead a sense of completeness settled inside.

Heading back up the Hume Highway I traced the origins of this journey, weaving the threads into the cloak of my psyche. The BMW had stuck tenaciously in mind in my early days of riding about 5 decades ago. My first motorbike was an old, black Suzuki Hustler 250, already nearly antique (clapped out), which I had bought for $200 from a friend. Initially it was for transport but I soon discovered the thrills and joy of two wheeled travel. I rode for fun through the twisting Galston Gorge and out to Dural in outer Sydney full of cruise and speed and cool. Concentrating and focused, it was intoxicating. It would struggle with belching blue smoke from the straining two stroke motor going uphill followed by the juddering downhill coast caused by mismatch from the chain, sprockets and engine. I met Cath and she sometimes doubled on the back, hands around my waist, close and soft and warm, yellow helmet, hair in the wind. Together we could conquer the world. “Baby we were born to run”. I got fed up with the smoke at about the same time I read “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance” which inspired me to take the whole motor apart, fit some new rings and put it all back together again. Working on it and fixing it (putting it back together) made me feel proud and capable. I loved being absorbed in the complex task and taking the risk to take it all apart. I was curious to learn as much as I could about the machinery and how things worked inside the motor. It still smoked like a bushfire. In the book Phaedrus rides an old BMW across America with his son and extolls all the wonders of German engineering, the boxer motor and the shaft drive. These became early threads – the joys of the ride, bike touring and the satisfaction of working on the mechanics.

Cath was also soon in need of a bit of maintenance and cash so I sold the bike for $200 with very mixed feelings to pay for her dental bills. In love and with no other cash there seemed no alternative. She had shared in part of my initial journey on motorised two wheels – it had felt like a comfortable comradeship.

We got hitched and then went to Africa, working as volunteer teachers at a school in Tanzania. We rode bicycles around for the first year, heavy clunkers, but pleased to have some mobility. Occasionally I’d notice an XT or XL 250 trail bike that was set up for touring the countryside. We were too poor to import a car or a decent bike but the notion of exploring the outback back home on a bike grew ever more powerful over those 2 years. In the second year we managed to get hold of an old CT 90 postie. We both dearly loved the red “postie bike” as it enabled us to travel around town during the day and night, arrive at school without a sweat and go on little excursions out of town. Two up was great with a seat for the rider and a flat metal tray for the passenger. These are very strong and capable machines equipped with a normal and low range gearing for loads and steeper terrain. Two adults and a huge basket of fruit and vegies from the market was no worries. It even had a switch on the air intake for high altitude which adjusted for a depleted oxygen content in the atmosphere.

The riding position felt almost easy rider style with higher and wider handlebars. It just felt so cool to be able to ride around on it. Occasionally we had to get spares posted from Australia which was hit and miss. Other volunteers and aid workers had access to diplomatic post which was reliable but we had to contend with only a fraction of our mail getting through. One vital spare was inserted into the cavity of a hollowed out book. It was nice as principal of the school to be able to travel and arrive at school in style wearing woven straw sunhats instead of helmets. Cath loved riding the postie as well. We both rejoiced in the mobility.

We were able to ride over and have Swahili lessons from Mr. Kopoku who was a retired university lecturer. He spoke the Queen’s best English with an Eaton accent and lived in a mud hut with a thatched roof in a village out of town. He was very refined and highly educated but had not been able to profit from the colonial history of the country which was one of the poorest 25 in the world. Conditions must be even worse now. Vestiges of good infrastructure like roads were already becoming very dilapidated in the early 80’s as the country had very little means of raising foreign currency through exports. Life’s injustices hit home as we would pull in to park our little red “limousine” each week in the shade of his overhanging thatched roof. Changing the world was a more complex business than we had expected.

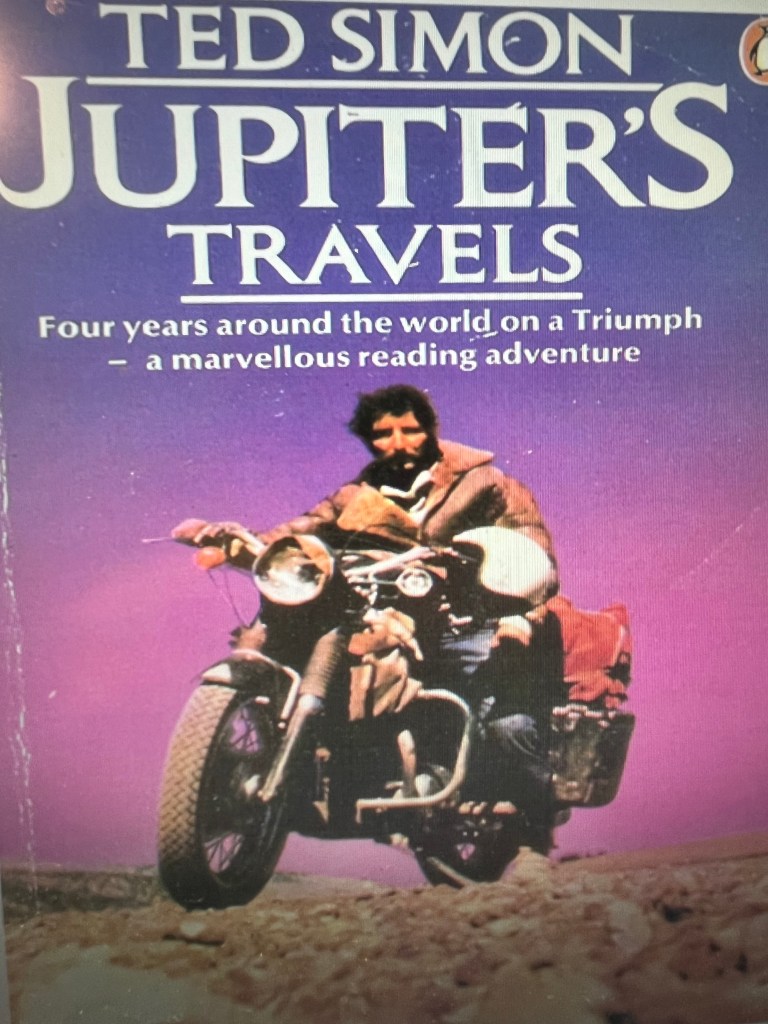

I read “Jupiter’s Travels” by Ted Simon while ensconced in Tanzania. His account of travel round the world on a Triumph inspired dreams of owning a decent bike one day that was capable of long-distance travel, maybe even to remote areas in Australia. Another strong thread wound itself tight into the weave.

On return to Australia we became immersed in our more affluent lifestyle and our mobility was provided for by full time well paid teaching jobs and a Ford Escort. The need for us both to have vehicles brought the possibility of a decent motor bike as a second cheap form of transport. I sourced a good deal on a Yamaha XT550 which was the best trail bike at the time. Brand new, yellow and white, 1985, I picked up the bike from Sydney and rode it home to Canberra through the rain and wind of a stormy night with Cath in the car in front. Smooth, shiny new and powerful but easy to ride. I couldn’t have been happier – all those longings from Africa finally achieved. I rode the bike to work at a suburban primary school and then later out to the country, to the outdoor school, from Canberra. About this time I started rockclimbing at Jervis Bay and sometimes travelled down on the bike loaded up with camping and climbing gear. This felt like the real thing. I also rode the 11 hour trip to climb in far west Victoria. I left after school at the start of a holiday period and intended staying by the side of the road somewhere on the way. I got into a groove and enjoyed the long ride and arrived about 4.00am cold and a bit spun out but well. Silly things you do eh? The only problem with the ride was the limited range of the smallish fuel tank, especially late at night. I was scared I’d get caught on empty at a small country town petrol station that had closed up for the night.

While working at the outdoor school a bigger version of the XT was released and I couldn’t resist updating by buying one from one of the other workers there – the XT 600 Tenere had a monster 30 litre tank and a range over 500 km. Unfortunately it was very tall in the saddle, had an intermittent electrical problem and was very top heavy. I learned a hard lesson that bigger was not necessarily better. I developed the skill of sliding my bum sideways on the seat to reach a foot to the ground every time I stopped. It looked like an obese mosquito. The biggest problem for me was the kick start. Because the bike was tall in the seat and I was short in the legs it was best for me to kick start it by standing it up next to a curb. The extra height gave me the downward travel kick to be able to start it mostly. It was hard to start anyway with 600cc of engine compression. If there was no gutter nearby I perfected the art of leaving it on the side stand then standing high up on the foot peg on the same side as the stand then launching down from a great height to try to kick it into life. My duties at the outdoor school where I worked required me to visit many schools for planning meetings. One visit took me to a suburban high school. I parked the bike outside in the carpark which was just flat bitumen and dirt outside the science labs. After the meeting I geared up and stood on the side peg then as I kicked mightily the side stand broke and the bike and I collapsed sideways onto the ground. I did not once look over towards the labs where classes of bored students were obviously watching out the windows. At the height of embarrassment I heaved the bike up and wheeled it down the road and out of sight round a corner to the nearest gutter and tried again. It had been pretty much a hassle from the start and to this day I think of the 550 as one of the nicest bikes I’ve ridden and owned. This had been a very powerful lesson that perhaps I would keep having to learn throughout life. Maybe I’m a slow learner in some things.

The ride out to the outdoor school for work involved 20km of winding country bitumen through the rural foothills of the Brindabellas. It took about a minute to clear the suburb then it was pure riding joy mostly. Often there were stunning light shows on the hills and peaks as the sun went down in the afternoon. I did this ride for about 10 years on various bikes (that means about 2,000 times out and back). It meant that Cath had the car and we were paying very little for the second vehicle’s expenses. In winter it was cold, freezing, but I never once tangled with ice on the road – only occasionally on the helmet. Good boots, gloves and finally a really good jacket kept the cold out most of the way. I decided to buck the normal trend of most bike owners and go for a smaller machine. I managed to get an almost new Suzuki TS185 which was a beaut little 2 stroke trail bike that tootled through the hills very nicely at about 75 or 80 kmph. Any faster and it struggled and blew smoke. It blended comfortably with the family finances, philosophy of the time and my slow zen style of happy riding.

I’m not sure which came first in about 1994 – the improved family finances or losing confidence riding. I often travelled from home to work in the hills at night and in the early mornings. There had been a spate of drivers from the outdoor school tangling on the roads with kangaroos. I knew the danger spots and always slowed right down but playing chicken with them eventually wore me down. The 185 was swapped for an old red Ford Laser. It had a stereo, heater(!!!), 4 sides and seemed the height of luxury. Through the next couple of decades I still harboured dreams of one day riding again – maybe on one of those shaft drive beemers. I daydreamed more regularly about desert rides but there wasn’t space or time or money – family, work and the mortgage took care of everything.

A long awaited big trip to Europe for Cath and I finally arrived after our children had grown up. I’d read “Vroom With a View” about an Australian guy who went to Italy and bought a very old antique vespa scooter and rode through the country from one adventurous breakdown to the next. He had seen Sophia Loren movies as a child and lived the dream with his own girlfriend. I thought we could do the same for a portion of our trip in Italy by hiring a scooter. Prior to the trip Cath arranged a friend of hers to let us have a ride on his new red vespa in suburban Canberra. This was fun and convinced us both of the viability of the concept. I did lots of research on the internet and booked a machine for a week in Tuscanny while we would be based in Sienna.

Having hiked the French alps and the Dolomites we made our way from our belltower room in old Sienna and went out early in the morning to the ancient walled town San Giminiano. At the hire shop I found out that contrary to the internet info theft was not coverable on the insurance arrangement. Worried about parking the scooter outside our hotel in the country of chronic scooter theft I was really disappointed and decided to take the scooter for only one day. Our whole week in Tuscanny was planned around little rides to outlying villages.

Off we rode into the day. It was nerve wracking at first in the traffic but once on the open rural roads our mood and worry lifted. The power was just enough and the countryside pretty but no better than the Hunter or Barossa. The villages were something else though. We pulled off the main road and scooted up to a hilltop settlement. The locals were preparing for a festival which was fascinating to watch.

A quick lunch and we were on the road winding through the fields and vineyards. The way on became a little confused by roadworks and so we stopped in at a rest bay to look over the map. I thought I knew which way to go but wasn’t sure. Pulling back out onto the road I was still distracted by thoughts of the map. A small car rounded the corner in front coming our way straight towards us. My first thought was that it was overtaking but it stayed on our side of the road and bore down on us at speed. In total alarm I took evasive action at the last minute and steered us onto the grassy verge. While coming to a bumpy stop the car passed with horn blaring and fists raised. Lack of concentration had taken me into autopilot on the left hand (wrong side for Italy) side of the road. We were breathing very heavily as we contemplated our futures still living and the shock the people in the other vehicle must have felt.

Maybe the insurance hassle was a good thing. The gloss of the scootering through Tuscanny lost its shine. I took solace in photographing some very old and cool vespas in Sienna, Lucca and Rome. Dreams come and go. The taste of pasta, wine and life was sweet.

I shared my desert ride idea over a few wines with a friend, Geoff, one night at a restaurant and instantly he said he was in, hands shaken and a date made, July 2011. No specifics but a lot of enthusiasm was shared. “I’d be there in a second”.

Christmas 2008. It was possibly a random nice present out of the blue but most likely a typical inspired piece of interpersonal intuition from my son Matt. The full “Long Way Round and Long Way Down” dvd set. I’d been vaguely aware of the tv show and the book but had tried to block it out for a long time as I knew it would be too painful to watch those well supported celebs ride my dream machine across the globe. With a sinking feeling of dread I settled in to watch the first episode with Cath and Matt. I was surprised and shocked at how absolutely riveting it was. They came across as enthusiasts and real people out to explore and adventure the world together. ON BMWs! I had done the right thing to avoid it for so long. It was too much to bear. When they met up with Ted Simon in Mongolia I nearly fell off the chair. The synchronicity for me was stunning.

Longing, dreaming, wanting, wishing, desire, sought after, covet, set one’s mind/heart on, aspire, think one deserves, crave, itch, hanker after, yearn, whet the appetite, allure, tantalise, affinity, zest, claim.

A financial teaching award in the mortgage and children independent now made the whole enterprise of motorcycling again a remote possibility. Some financial twisting could bring it close without making too much of an impact.

Could I do this? Spend the money? Did I deserve this? Would it reflect the value of me like a reward as a kid? What would the reward be for? – A life’s work trying to change the world, trying to make it a better place? For helping young people build exciting things into their lives that are wholesome and good? “Young people have a void inside them that is aching to be filled with something challenging and exciting”. As I drove up north towards Crescent Head, leading a surf trip, and a student selected one of my favourite Hendrix tracks that rocked the bus, time shifted and deep memory of my own aching void connected directly to a key point in my youth “at seventeen” – surf, friends, meaning. Maybe a successful life is to hold on to those seminal experiences of youth, to build from them and stay in touch.

Would it be a reward for being a dad and a husband? Isn’t it just enough? Where did a life’s interest in philosophy get me to? Is satisfaction with one’s life and self like zen? Where is true freedom and what is highest order living? Or is it like a little death to cruise along like a ghost on a quiet ride of resignation and acceptance. Longings don’t get easier with age they get bigger, deeper and harder. Was I a “victim of society” as Spirit sang, of being sucked in wholus bolus into the consumer material world? Could I justify the resources in this world of the poor that I have seen and the ecological danger that I taught about? Getting old/er. Beard turning grey – is this another case of looking older than I am or feel? Leave it be. Let it go. Don’t wait til it’s too late. Big boy’s toys would help reconnect me with my own inner little boy exploring the bush, the world, on his bike. Now bigger dreams. Bigger landscapes. Deserts and outbacks. Journeys and thrills. Is this what a mid-life crisis is? A balancing act?

A daily dual – body, mind, heart – technology, handling, power.

The sound and feel of the wind throwing off the grind or capping off the goodness of the day.

Twist of the wrist and the speed focusses. Concentration shuts out all else. In the zone.

The daily duel – staying safe.

Riding near the edge enriches life.

Merging, being one with the journey.

This duel played out in my head several days a week for several more years. Caught in the grip of indecision until work and family shuffled it all into the background again.

Eventually I retired from full time work at age 58. I had a bit of long service leave left and got a payout for it separate to superannuation. I met up with a friend from work over coffee and eventually we talked about biking. I shared my long term dream to ride remote Australia especially the desert and arid regions. Kim had been a biker in his youth and yearned to ride the outback as well. I can’t remember if we shook hands on it or not. Quick to action he turned up with a monster VStrom 1000! His riding skills were fabulous.

After researching adventure bikes for ages I settled on a new DR650 – Unbreakable, reliable, lightweight, great off road, spare parts everywhere, powerful enough, suspension could be lowered for my short legs and just affordable.

Kim and I had lots of adventures in the Canberra hinterland and beyond. Totally fab fun. We planned a big desert trip out to Uluru the following year.

My brother-in-law, Chris, had his interest sparked. Pretty much never having ridden a motorcycle before he bought an old postie bike and got a license in about a month then traded up to a KLR 650 which was a bit top heavy but a similar workhorse to the DR. A friend of his, Paul, joined in on another DR. Kim had a medical issue right before our big trip so he had to pull out. We had a team of three.

Broken Hill, Tibooburra then challenging sandy roads to Cameron Corner. 50km into the Strzelecki Desert the KLR developed a radiator leak. Turned around and limped back to broken Hill. Repairs. We rerouted over to the Flinders Ranges then up the Oodnadatta Track and into the stark beauty of Lake Eyre. Pink Roadhouse.

Fixed a punctured tube in the Painted Desert then out to the blacktop and up to Uluru. Kings Canyon then onto the notorious Merinee Loop. Climbed Mt Sonder. In Alice Springs Paul headed off into misadventure on the Plenty Highway stones. Chris and I headed home via Woomera and Mildura on the bitumen – cold and damp back into winter. Eventually Paul made it home a little broken up. The trip had been amazing – riding in a group, landscapes of iconic dreams, wide spaces of the outback, quirky towns and settlements, 3 weeks of blissful riding. And plenty of badass/sore arse. The DR ate it up. We all ate it up. Learning, stretching ourselves, immersing.

Indestructable?

Another friend joined our Mild Hogs group, Greg, on another DR which was preceded by Chris’s old postie bike. It was a dream of his too to ride out across the land with a group of mates.

The following year Kim joined us on a GS 650 as we ventured again through the Flinders, bogged ourselves in the sand on the way into Lake Frome, Arkaroola then up into the Strzelecki. Innaminka, Burke and Wills Dig Tree. Then with the track only just reopened we rode mud and crossed creeks on the way to Tibooburra. 30 km from the safety of a better road Kim tumbled and flying doctored back to Broken Hill and home. Up until that point the trip had been an absolute cracker. Kim recovered and even fixed up his GS 650. Chris shuffled his KLR for a new DR (no radiator). Then Geoff joined us on another DR.

The next big trip required us to reverse our itinerary to dodge bad weather. Nyngan, Bourke, Gundabooka. Then along the famous Darling River Run 4WD route to Wilcannia, Mootwingee and then Broken Hill. Camped by Menindee Lake in Kinchega, Wilcannia again due to the rain, down to Ivanhoe, Hillston and all home safe.

Greg transferred his interest to a Harley. Kim bought a third bike, a whistling Triumph 900 then changed this for a GS 1200, which opened up a niggling itch for me. Geoff switched onto a big Moto Guzzi adventure tourer. Paul upgraded from his very old black stallion DR to Geoff’s newish one.

My DR had a shocking rattle from the front that felt at times like the engine was about fall out. It got hard to start after a break which was annoying and worrying. I had a ride on Kim’s GS 1200 and found it delightfully smooth and powerful and not too tall. The BMWs, though big and heavy, were renowned adventure bikes with a low center of gravity and that beautiful shaft drive. An 800 with that design would have been perfect but didn’t exist. I managed to pick one up at a good price and did what I could to lower it to a comfortable height. Yes it was an elephant to walk around with but once you were riding it was the dream. Bluey and I had teamed up. I persisted to overcome the “bigger is not always better” lesson.

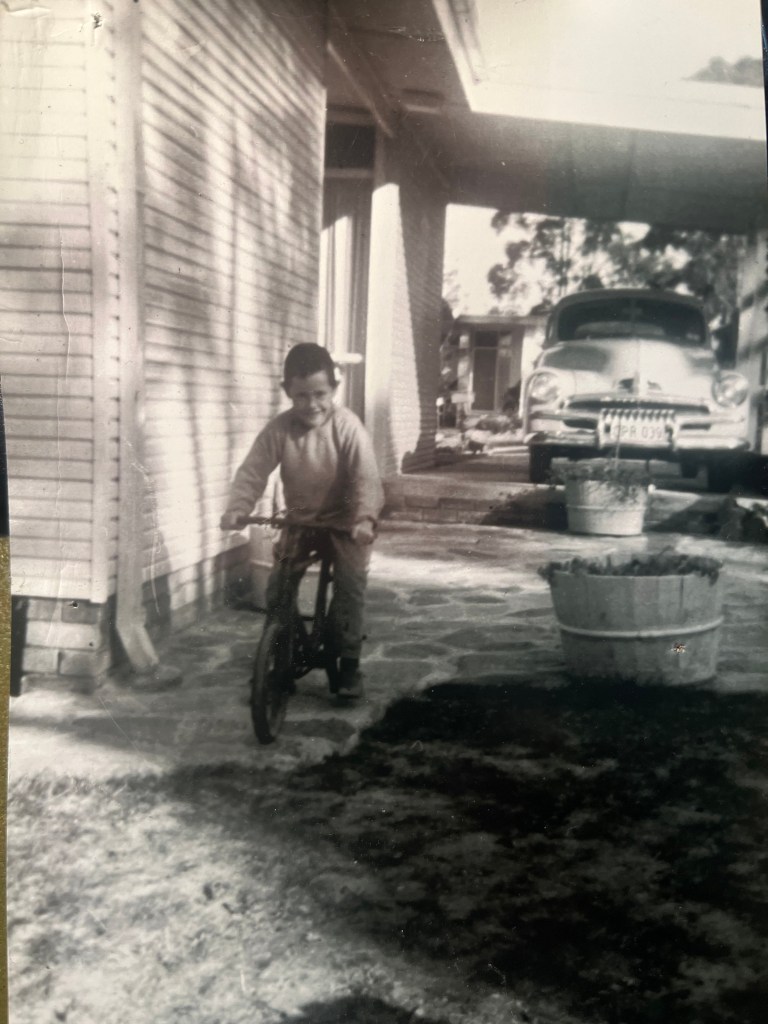

When I was a child of about 5 or 6 I was given a very old hand-me-down bike with solid rubber tyres on the wheels. I hooned endlessly round the back yard tearing up the grass and making tracks. This was followed later by a bike with pump up tyres and an independence that stretched out into the bush as the suburb grew its boundaries in step with my growth in stature. Spare time I spent exploring all the tracks, fire roads, bush and building sites within an expanding reach. I discovered and reveled in exploration and freedom and found secret spots down in the bush only I knew about. I was at ease and always had a sense of excitement at what I might find. Independence and autonomy.

I realized, as I cruised up the Hume past Yass, following Marc and Chris, that in my 60 years of riding, each time I set off on my bike I was revisiting that small boy, feeling the same anticipation and thrill. Honouring all my younger selves was the final thread that took pride of place in my cloak.

Stand up. Lean forward a little.

Hold on with your legs.

Arms relaxed and elbows bent outwards.

A little throttle, keep momentum up.

Look ahead.

Breathe.

A goofy smile.

“OOH YEAHHH!”

And as Angus says to Demon in Demon Copperhead “Trust the ride”. Barbara Kingsolver

Home. Warm. Safe.

Further info for Adventure Riders, readers and music fans

Useful links

- Outback Roads SA https://www.dit.sa.gov.au/OutbackRoads

- Closed roads Sturt National Park https://www.nationalparks.nsw.gov.au/visit-a-park/parks/sturt-national-park/local-alerts

- SA Desert Parks https://www.parks.sa.gov.au/campaigns/desert-parks

- Cameron Corner store https://www.facebook.com/p/Cameron-Corner-Store-100057203179555/

Songs

- “Under the Milky Way” – The Church

- “Born to Run” – Bruce Springsteen

- “Raining on the Rock” – John Williamson

- “Mango Pickle/Down River” – Wilcannia Mob

- “Wide Open Road” – The Triffids

Books

- “Why We Ride” – Mark Barnes

- “Jupiters Travels” – Ted Simon